|

U.S.

STRATEGIC INTEREST IN SOMALIA: From Cold War Era to War on

Terror

(Mugdisho,

October 23,

2010 Ceegaag Online)

Thesis written by: Mohamed A.

Mohamed | 01 June 2009

Nominated as TFG Prime Minister on October 14, 2010.

Contact: Office of the Prime Minister TFG Somalia

Email:

pmcommunicationoffice@gmail.com

U.S. STRATEGIC INTEREST IN

SOMALIA:

From Cold War Era to War on Terror

by

Mohamed A. Mohamed

01 June 2009

A thesis submitted to the Faculty

of the Graduate School of the State University at Buffalo in

partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree

Master of Arts

Department of American Studies

"I object to violence because

when it appears to do good, the good is only temporary; the

evil it does is permanent."

Mahatma Gandhi

Table of

Contents

Abstract

Chapter 1

Introduction

- Dynamics of

Clanship in Somali Society

- European

Colonial Rule

Chapter 2

U.S. Strategic Interest in Somalia during the Cold War Era

- U.S. and Soviet

Union in Somalia

- The Rise of

Warlord Phenomena in Somalia

- U.S. Support

for Somali Warlords

Chapter 3

Global War on Terror - Post 911

- The Rise of

Islamic Movement in Horn of Africa

- The Role of

Ethiopia in Somalia

- Conflicts

within Somali Government

Chapter 4

Failed U.S. Policy in Somalia

Bibliography

Abstract

This thesis

examines United States' policy toward Somalia from the era

of the Cold War to that of the more recent and ongoing War

on Terror. It asserts that U.S.'s change of policy from Cold

War alliance with Somalia to the use of Somalia as a

battleground in the War on Terror has resulted in a

disorganized and disjointed policy framework. In 1991, an

alliance of warlords defeated President Siad Barre's regime

that supplied Somalia's last central government and that was

allied to the US. Subsequently, the victorious warlords

turned on one another, resulting in clan feuds that

destabilized the Somali state. In March 1994, this chaos

engulfed US troops engaged in a humanitarian mission,

resulting in the death and humiliation of several American

soldiers in the so-called Black Hawk Disaster that led to

the withdrawal of US troops and interests from Somalia.

However, following the events of September 11, 2001, in

which Islamic extremists attacked the Twin Towers in New

York City and the ensuing launching of War on Terror, the

United States became suspicious that Somalia was now a

breeding ground for terrorist attacks against American

interests in East Africa. This threat increased when Islamic

Court Union (ICU) consolidated its power in southern Somalia

after defeating US-allied warlords in June 2006. The ICU did

bring a respite of law and peace for some six months,

following fifteen years of warfare and chaos. But this was

short-lived. Armed with economic and political support from

Washington, neighboring Ethiopia invaded southern Somalia

and occupied Somalia's capital, Mogadishu, under the pretext

of the War on Terror. As many as 1 million people are

reported to have been displaced and more than 10,000 were

estimated to have been killed in Mogadishu.

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Dynamics of Clanship in Somali

Society

It is

imperative to understand Somali history, society, and

culture in order to evaluate U.S- Somali relations during

the Cold War and War on Terror. Somalia is located in the

Horn of Africa, adjacent to the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian

Peninsula. Historically, it was similar to numerous cultures

in and around the region. For example, in ancient times, the

Egyptians glorified Somalia as a "God's Land" (the Land of

Punt);1 Greek merchants who traveled on Red Sea

called it the "Land of Blacks." Arab neighbors used to refer

to this land as Berberi. German scholars observed that the

Samaal people, who give Somalia its name, inhabited and

occupied the whole Horn of Africa as early as 100 A.D.2

This theory diverges from the popular myth that the Somali

people (also known as Samaale or Samaal) originated from

Arab roots.3 Indeed, historians and archeologists

have revealed that Somalis share language, traditions, and

culture with Eastern Cushitic genealogical groups.4

The Eastern Cushitic ethnic sub-family includes: the Oromo,

most populated ethnic group in Ethiopia; the Afar people who

inhabited between Ethiopia and Djibouti; the Beja tribes of

Eastern Sudan; and the Boni tribes of Northeastern Kenya. In

other words, modern Somalis are richly embedded in African

culture.5

-

1 Jacquetta Hawkes,

Pharaohs of Egypt

(New York: American Heritage, 1965), 27.

-

2 Helen Chapin

Metz,

ed. Somalia: A Country Study (Washington, D.C.: Federal

Research Division Library of Congress, 1992), 5

-

3 Ali Ahmed, The Invention

of Somalia (New

Jersey: The Red Sea Press, 1995), 5.

-

4 Lee Cassanelli, The

Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a

Pastoral People (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

, 1982), 23

-

5 B. Lynch & L. Robins, New

Archaeological Evidence from North-West

Kenya.

(Cambridge University Press, 1979), 320.2

The four

major tribes of Somali lineage are nomadic and pastoral:

Dir, Darood, Isaaq, and Hawiye. These nomad tribes

constitute around 70 percent of the Somali population. The

two smaller agricultural tribes - Digil and Rahanweyn - make

up only 20 percent, while 10 percent of the population is

comprised of coastal dwellers whose economy is based on

fishing and farming. It is imperative to understand the role

and history of clan politics and how it developed over the

centuries to shape the modern government in Somalia.

Traditionally, nomadic society mastered the art of forming

alliances to protect the interests of kingship and ensure

water and grazing land. Rainfall, in particular, is very

critical to the life of pastoral communities. It is the main

factor that forces them to compete with other tribes and to

move from one inhospitable place to another. Although they

expect two rainy seasons, some localities never see one drop

of rain and experience severe droughts, costing nomads most

of their livestock. In the 20th century, there were six

harsh droughts across several regions of Somalia that lasted

more than two years and produced famine.6

Tribal

elders play an important role in the process of securing

water. They make the final decisions in waging war and

making peace with other neighboring tribes and relocating

clan-families to new territories.7 Tribal elders

sit on the council of leadership that administers most clan

affairs, down to relatively small matters, like marriage

arrangements within the clan-family. The relationship

between different tribes always depends on how tribal elders

manage conflicts and enforce previous agreements. However,

an agreement might not last long. Therefore, it is the role

of elders to find some sort of resolution to crises before

things get out of hand and an endless cycle of revenge

ensues. It must be said that these tumultuous situations and

conflicts are positive in that they cement together

clan-families against the threat presented by other tribes.

This is necessary, as with political circumstances shifting

continuously, it is hard to predict when another skirmish or

war might take place. Yet, insecurity and suspicion within

the clan remains high where negotiation and conflict

resolution are not possible. In his book, Lee V. Cassanelli

summarizes Somali clan politics by translating Somali

proverb:

I and my

clan against the world

I and my brother against the clan

I against my brother8

-

6 I. M. Lewis, Brief

descriptions of the major Somali drought in the 20th

Century, including that of 1973 -75, can found in Abaar:

The Somali Drought. (London,

1975) pp. 1-2, 11-14.

-

7 While anthropologists

might use tribe and clan in different terms, in Somali

language, both (clan-family and tribe) mean the same.

-

8 Cassanelli, 21

European

Colonial Rule

Over the

centuries, the Somali people have demonstrated, as part of

their tradition, a vigorous independence and unwillingness

to surrender to a single political authority. Clan leaders

never quite had the authority to enforce rules on all

people; rather, their role was to remind people of the

importance of strong clan consciousness, stressing ancestral

pride, as the clan has been the integral part to their

survival and existence since ancient times.

It is

important to discuss the reaction of Somali nomadic society

to the European-introduced modern Somali state. A clash of

cultures invariably resulted from different conceptions of

law as it relates to the person. The European concept sees

the state as responsible for individual rights; inherently,

it does not recognize the nomadic system of justice, based

on collective responsibility. Over the centuries, the Somali

coastal area has entertained various outside rulers,

including the Omanis, the Zanzibaris, the Sharifs of Mukha

in present day Yemen, and the Ottoman Turks. One thing these

rulers had in common was that they did not disturb the

nomadic lifestyle or interfere in their clan-family

politics, because they knew Somalis were used to being

ungoverned and therefore suspicious of foreigners. However,

everything changed when the Somali Peninsula and East Africa

were dragged out of relative isolation into world politics.

This was only the start of the imperial epoch. In 1885,

rival European powers - Great Britain, France, and Italy -

divided amongst themselves land populated by the Somali

ethnic group in the Horn of Africa.9 This territory was

essentially ruled by clans until Great Britain took the

northern territory near the Red Sea, close to its other

colonies in Aden; while the least-experienced European

colonies, Italy, was granted Southern Somaliland. The French

took hold of what is today known as Djibouti, a tiny nation

on Red Sea. Ethiopia also grabbed a chunk of Somali land

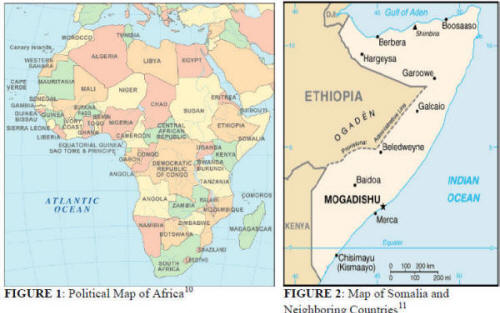

called the Ogaden (see Figure 1 & 2).

-

9 Scott Peterson, Me

Against my Brother: At War in

Somalia, Sudan, and Rwanda

(London: Routledge, 2000), 11

The British

and Italians had different strategies and interests in

Somalia. Britain was interested in Northern Somalia,

mainly as source of livestock for its colony in

Aden,12

its principal supply route to

Indian Ocean through the Suez

Canal. British occupied Aden

in 1839. Italians, on the other hand, wanted crops in the

form of plantation agriculture: bananas, sugarcane, and

citrus fruits. As soon as the British colonial government

started asserting its authority over Somalia at the turn of

the century, resistance took shape under the leadership of

Somali nationalist Sayyid Mohammed Abdille Hasan: known to

the British as "the Mad Mullah".13 His Islamic

resistance movement sought to end European rule and

Ethiopian incursion in Somali territories. He used both

religion and nationalism to advance his cause and

successfully united Northern Somali tribes against the

foreigners until his death in 1920. The use of force by

British never produced a better outcome, but Sayyid Mohammed

won many followers, especially among his own clan. He dared

to suggest the possibility of a free and united

Somalia. While British and

Italian colonies were vying for control of the Somali

Peninsula during the World War II, Somalis continued to

mistrust and undermine the authority of their colonial

rulers. As a result, the first modern Somali political group

was formed in 1943. The Somali Youth League (SYL)

articulated the need for national unity and, by extension,

discouraged division and feuding between clan-families. This

new ideology worked; the SYL helped Somalis realize that the

only way to succeed and overcome colonial occupation was to

unite against it.14 Against a common rival, a

national consciousness was beginning to form. The political

pressure also helped to improve lives: colonial rulers took

steps for economic development, better education, and

healthcare for growing urban communities. The SYL's main

focus, of course, was to end colonial rule and liberate the

nation from foreign influence and domination. This did not

happen overnight; however, the organization succeeded well

in easing ill-feelings between tribes and compromising the

clan system. The creation of a Somali state in 1960 could

not have happened without this foundation.15

-

14 M. I. Egal,

Somalia: Nomadic

Individualism and the Rule of Law (Oxford University

Press, Jul., 1968), 220

-

15 B. Braine, Storm Clouds

over the Horn of

Africa.

International Affairs (Royal Institute of International

Affairs, Oct., 1958), 437

CHAPTER 2

U.S. STRATEGIC INTEREST IN

SOMALIA DURING THE COLD WAR ERA

The U.S.

and Soviet Union in Somalia

U.S

involvement in Africa was limited before World War II, with

the exception of a few commercial treaties signed with

selected countries in West Africa. Generally speaking,

Washington was not interested in African affairs and voiced

no real objection to European domination of the continent.

However, there was some attention to Africa when, on January

18, 1918, President Woodrow Wilson offered his famous

Fourteen Points declaration to a Joint Session of Congress

in which he spoke about the principle of self-determination

and governance.16 At that time, President Wilson

wanted to counter the German threat which had changed the

American attitude toward European Colonies. His stance had

obvious implications for the millions of Africans subjected

to foreign rule.

-

16 Paul Johnson, Modern

Times: The World from the Twenties to the Nineties (New

York: HarperCollins,1991), 429

-

17 Ibid., 21

The Atlantic

Charter, signed in 1941 by President Franklin Roosevelt and

Prime Minister Winston Churchill, was another initiative to

promote world peace by compromising imperialism. Both

leaders recognized the importance of colonial people's

rights to self-determination and self-governance. 17

After World War II, the Soviet Union entered world political

affairs in opposing Western domination and imperialism. As a

result, the Western bloc became still more proactive in

promoting democracy in the former colonial countries.

World War

II's end marked the beginning of de-colonization in Somalia

in earnest. The process was not always perfect. Upon Somali

independence in 1960, British Somaliland and Italian

Somaliland united under one flag, yet colonial boundaries

granted Ethiopia, Kenya, and France control over territories

in which ethnic Somalis make up the majority of the general

population. While these three countries remained allies of

the United States, the U.S did not want to sever relations

with Somalia because of the Soviet threat and strategic

importance of Africa's Horn region. As a result, the U.S

promised financial and military aid to Somalia; however, the

Soviet-led Eastern bloc also offered a similar deal in

pursuit of its geographic advantages. Thus, Somalia became a

prize during the Cold War; even President Kennedy recognized

this development and met with Somali Prime Minister

Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke in 1962. However, the Soviet Union

ultimately offered what Somalia wanted most: more military

hardware (the Russian military aid agreement of 1963) to

protect the Somali population in Kenya and Ethiopia.18

On October 21, 1969, the armed forces, led by General Siad

Barre, overthrew the civilian regime (former democratically

elected leader Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke was assassinated by

one of his own security guards during his visit in the

drought-stricken area of the Las-Anod Disrtict, in the

northern part of Somalia). Quickly, the usurping government

adopted scientific socialism, nationalized all major private

corporations, prohibited political parties, and shut down

the parliament. U.S influence in Somalia apparently ended as

Somalia and the Soviet signed a prestigious treaty of

friendship.

On November

1, 1969, General Siad Barre established the Supreme

Revolutionary Council (SRC). The organization announced its

intention to fight and abolish tribalism and nepotism, major

obstacles to progress and growth in the nine years of

civilian, democratic government. The nation was in perpetual

financial crisis and overly dependent on foreign assistance

to meet its operating budget. A majority of Somali people

welcomed the new military regime's promise to clean up the

sort of corruption that had been tolerated in the previous

administration. Popular acceptance helped facilitate Barre's

initiatives like "Scientific Socialism" and the battle

against tribalism, thought to be the true cancer of Somali

society. Indeed, an official government slogan stated,

"Tribalism divides where Socialism unites."19

-

18 I. M. Lewis, Modern

History of Somalia (London: Westview Press 1988), 209

-

19 I. M. Lewis, Modern

History of Somalia (London: Westview Press 1988), 209

-

20 Metz, 119

The new

government won the hearts and minds of the people by

promoting a new self-reliance and self-supporting mentality.

This helped to encourage a national, rather than clan,

consciousness, for it lessened dependence on traditional

clan lineage for survival. The main dream for every Somali

was to be unified, including those living under Ethiopian

and Kenyan rule. Over the first eight years of the Barre

regime, the Soviet-Somali relationship grew into a

significant military alliance. The two countries signed an

agreement that brought Soviet military capabilities to

Somalia. Numerous, sophisticated Russian weapon systems

appeared, including MiG-21 jet fighters, T-54 tanks, and

SAM-2 missile defense system.20 In return, the

Soviets were allowed a base at the port of Berbara port,

near the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. From this strategic

location, they could counter United States military movement

in the Middle East and North Africa and control trade. A

more sinister aspect of the agreement saw the Soviet Union's

KGB training Somalia's own secret police organization, the

National Security Services (NSS), which could detain people

indefinitely for any manufactured allegation.21The ambition

of a greater, stronger Somalia come to fruition when Siad

Barre invaded Ethiopia to liberate the ethnic-Somali Ogaden

region in 1977. Ironically, the 1977-8 Somalia-Ethiopian

War, enabled by Soviet support, was the severing point in

the friendship between the Cold War nations. The Soviets

elected to support Ethiopia against the nationalistic plans

of its audacious neighbors. The Somali National Army lost

the war when a full Eastern bloc (comprised of Cuba, East

Germany, Libya, South Yemen, the Soviet Union army) attached

themselves to the Ethiopian cause. Of course, Somalia was

not doomed to float out at sea. In a polarized world, a

Soviet enemy was automatically the United States' friend.

Here, Washington found an opportunity to normalize relations

with Mogadishu. It offered military equipment to Somalia in

order to counterbalance Soviet and Cuban support for

Ethiopia. Somalia, built by Soviet aid, joined the Western

camp in 1978, thus verifying the old cliche' that there are

"no permanent friends nor permanent enemies."

During the

Cold War, the United States had a definite history in its

African Enterprise of supporting ruthless dictators, who

committed atrocities and violate the fundamental human

rights of their own citizens. It was only required that

these thugs somehow suit American interests. This policy has

long compromised key principles of the Constitution: due

process of law, respect for individual freedom and human

rights, free and fair democratic elections, and a free

market economy. Yet such opportunism remains a fixture of

American foreign policy. Somalia fits the trend. Despite

Siad Barre's poor human rights records and corrupt

government, the United States provided him with the economic

aid to sustain his government and military aid to protect

Somalia from Ethiopia's hostile Marxist regime. Here, one of

many American-Soviet proxy wars was waged where mutually

assured destruction prevented a direct clash. Like Zaire's

notorious Mobutu Sese Seko, Barre benefited handsomely from

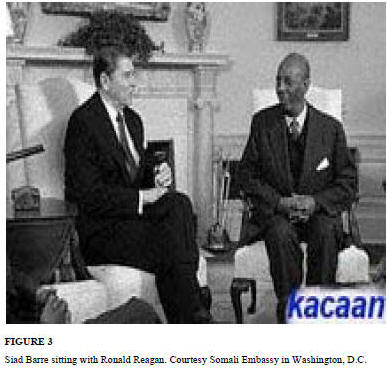

America's support and blind eye (see Figure 3). His regime

survived the 80s, receiving grants and flexible loans from

the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), and

food aid through USAID22, which was distributed amongst

camps and displaced communities, as a result of a refugee

flood from war-torn Ogeden region of Eastern Ethiopia. In

return, the United States received its strategic naval base

at Berbera.

-

22 Graham Hancock, Lord of

Poverty: The Freewheeling Lifestyles, Power, Prestige, and

Corruption of the Multibillion Dollar Aid Business.

(London: Macmillan London Ltd., 1989), 24

Strategically speaking, this was a win-win situation between

the two allies. However, Barre's gloomy shadow lingered over

American integrity. Here was an illegal dictator who neither

tolerated political opposition nor so much as attempted to

compromise in crafting solutions acceptable in all parties.

Rather, he preferred to act as a thug, using force to

eliminate any clan-family sympathizing with the opposition.

His military forces committed unnecessary atrocities in

central Somalia in particular, where they burnt villages,

slaughtered thousands of innocent people, and raped women.

Barre was highly antithetical to what the United States was

supposedly pursuing. It is no wonder that, in mid 80s, a

rising opposition movement demanded fair representation in

the government. When Barre ignored this element, the

opposition armed itself as the insurgent Somali National

Movement (SNM), its aim simply to overthrow the Barre

regime.23

-

23 Ahmed

I.

Samatar, The Somali Challenge: From Catastrophe to

Renewal? (London: Lynne Rienner, 1994), 118

The SNM's

guerrilla army briefly seized two major cities in Northern

Somalia - Hargeisa and Buro - in 1988. Barre and his

superior American weapons reacted by emphatically crushing

the SNM movement. He essentially leveled the rebel cities.24

Many civilians died in the crossfire; thousands more fled

their homes for the countryside, where water and shelter

were short.

-

24 Anna Simons, Somalia and

the Dissolution of the Nation-State (American

Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 96, No. 4, Dec., 1994),

823

-

25 Scott Peterson, Me

Against my Brother: At War in Somalia, Sudan, and Rwanda

(London: Routledge, 2000), 15

-

26 Samatar, 121

When the

Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991, so too did the

polarization of the world. The United States no longer had

any real need for Somalia. It was now convenient to withdraw

the support that had long enabled Barre's rule and the

illegalities that characterized it. When the United States

suspended all financial aid to the Barre's regime, his

security apparatus swiftly collapsed. Sensing the regime's

vulnerability, rebel forces - taking the form of the United

Somali Congress (USC) - led by Mohamed Farah Aideed stormed

Mogadishu. Barre fled the capital in January, 1991.25

With the shared enemy eliminated, so too did any reason for

the resistance movement to be unified. The same warlords who

brought down the dictator continued to fight among

themselves for power and control; thus regional, clan

politics returned to Somalia at the worst possible time.26

The United

States neglected its former Cold War ally until the

September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Now, embroiled in

another global conflict, the United States found new

strategic interest in Somalia and the Horn of Africa. This

time, aid was offered to Somali warlords and former Somali

rival, Ethiopia, to fight America's proxy war. President

George Bush announced that Ethiopia could serve as an

important strategic ally against international terror

networking. Therefore, in 2005, he oversaw a $450 million

donation in food aid, engineered by the U.S. Agency for

International Development.

The Rise

of Warlord Phenomenon in Somalia

The warlord

phenomenon started soon after the collapse of the central

government in Somalia in 1991. This was the era of the

United Somali Congress (USC) rebel movement, characterized

by much unfortunate chaos and violence. When USC leadership

(predominately from the Hawiye tribe) could not reconcile

its political differences, it descended into infighting

which took the form of outright war, given that the USC was,

in fact, a tribal militia at heart. This struggle had two

sides: one side was loyal to self-appointed president Ali

Mahdi Mohammed and the other side to General Mohamed Farah

Aideed. For a year the power struggle afflicted the Somali

people with loss of lives and property. The two men's

quarrel became everyone's problem. Too often, this is the

case in modern-day Somalia. Neither leader could claim a

decisive victory or take control of government institutions.

Consequently, peace and security in the nation's capital

were threatened.

These

leaders were entrapped in Somali tradition. They exploited

that tradition while bearing the guise of modern diplomacy

and tact. They effectively turned the struggle for control

of the USC into a fight for clan supremacy. The combatants

recruited fighters from their own clan-families and

committed themselves to clan, rather than Somali nation

interests.

Aideed and

Mahdi were vying for presidency of the entire nation.

Although their collaboration had already toppled the Siad

Barre regime, they did not understand that compromise

worked. Now they had worked together to defeat a

dictatorship: each settled to become a local political

leader of his respective clan-family in the hope he would

thereby control government institutions for the benefit of

his own sector of the Somali people. Interestingly, the two

"candidates" were members of the same Hawiye tribe of

Mogadishu and central Somalia. Aideed belonged to

Habar-Gidir sub-clan family, while Mr. Mahdi was a member of

the Abgal sub-clan. Thus, General Aideed and Mr. Mahdi

subdivided Hawiye tribe into two sub clans over which they

presided as warlords. This development marked a "slippery

slope" which was incompatible with the modern nation-state.

Hence, "Warlordism" became an accepted part of Somali

political culture. With so much threat from other clans,

every major clan-family had to grow its military leaders and

militias in order to protect itself. After all, the

government itself was infested with warlords. So there was

little protection - let alone examples of good state

governance - coming from the Somali State Capital.

In summary,

while clan elders and chiefs were still responsible for clan

family affairs in villages, warlords were the players upon

the national stage. They kept away from clan business which

might create conflicts with traditional elders and chiefs.

The warlords concerned themselves with warfare; they knew no

other way of getting things done. In effect, they were - and

still are - Somalia's nightmare, an unending plague.

U.S.

Support for Somali Warlords

The United

States reevaluated its foreign policy following the Soviet

collapse and the subsequent end of the Cold War. Somalia

marked one of the changes. Since there was no longer

significant strategic importance to the Horn region of

Africa, the U.S. ended all economic and military aid to Siad

Barre's regime, leaving him with no leg to stand on.

Encouraged, insurgents rose to armed struggle against the

demoralized and poorly equipped national army. Suddenly,

Barre's government resembled a pushover. It quickly ceased

to existed, but the transition was less than ideal. Somalia

went from one to many rulers; already in battle mode,

warlords took to fighting each other where there was no

Barre to unite against. Thus, anarchy replaced law and

order. Somali went back to traditional clan warfare. This

sort of chaos was part of the old, nomadic culture but

hardly compatible with the requirements of a modern nation

state. The clan-family system and its culture of violence

took its toll. Major clan-families aligned themselves behind

warlords. All seeking protection of their own interests and

territories, they wound up infringing heavily upon each

other, fueling a prolonged civil war in the country.

Countless innocent people lost their lives because of the

fighting. More severe, however, was the starvation it left

in its wake. 1992 saw a historic famine. A full quarter of

Somalia's nine-million people experienced malnourishment.

Here, conscience got the better of the United States and

international community. The United Nations took up a

humanitarian intervention geared at getting help to starving

people in the countryside. This was easier said than done.

It quickly became apparent that the United States could not

aid Somalia without embroiling itself in the civil war.

Warlords were blocking United Nations' aid shipments from

reaching people in need. President George H. W. Bush's

administration introduced a new initiative called "Operation

Restore Hope" before it left office in late 1992. This

effort saw the United States partner with United Nations

Secretary-General Boutros Boutros Ghali in the deployment of

30,000-strong peacekeeping force to oversee safe and

effective delivery of humanitarian food to the starving

people. President Bush went to the town of Baida, which the

media had dubbed "City of Death," to witness what the effort

was accomplishing - and exactly what it was up against.

Bill Clinton

replaced George H.W. Bush in office in 1993. He continued,

and in fact expanded, his predecessor's involvement in

Somalia. Now the humanitarian mission started to turn into a

political and nation-building effort.27. However,

in pursuit of the best government, U.N. and U.S. officials

actually helped to exacerbate strife by pitting one warlord

against another. One prime example was when Belgian

peacekeepers enabled warlord Mohamed Said Morgan to capture

the southern Somali town of Kismayo from General Mohamed

Farah Aideed's ally, Mohamed Omar Jess.28 This action

infuriated Aideed and his followers (see Figure 4). Many

violent protests ensued against U.N. humanitarian efforts,

involving road bombs and skirmishes with Pakistani

peacekeepers.

-

27 Craig Unger, The Fall of

the House of Bush: House of Bush, House of Saud. (New

York: Simon & Schuster, 2007), 176

-

28 Peterson, 65

-

29 Aideed's photo was

retrieved from http//www.hobyo.net

Here, U.S.

policy completed its transformation from a humanitarian to

military mission and ordered the arrest of General Aideed.

This mistake shows the extent to which the United States

failed to understand the culture and the clan politics of

this nomadic nation. Admittedly, Aideed was a ruthless thug

and a poor model for humanity; yet when U.S. and U.N

coalition started to hunt him down, he became an automatic

hero for Somalis because of his wiliness to stand up to the

world's remaining superpower. As mentioned before, there has

always been conflict among tribes; however, as soon as a

foreign threat manifests itself, old clan rivalries give way

to unity against the common threat. The clans, after all,

are separate pieces of one shared, regional culture; here is

where they become Somali.

Aideed

mobilized Somalia's clans, including rivals, against the

foreigners. In response, the United States and United

Nations escalated the conflict. This led to eighteen

American servicemen losing their lives and the infamous

shooting down of two Black Hawk helicopters.30

The nation-building effort never succeeded because of

misunderstanding of Somali culture and misguided foreign

policy based on unnecessary use of force rather than

political resolution. The war became an embarrassment to the

Clinton administration especially, particularly when images

surfaced of an American serviceman being dragged through the

street of Mogadishu. This was about enough. President

Clinton admitted the failed U.S. policy toward Somalia and

announced that he was bringing forces home.31 In

1994, U.S. and international forces left Somalia, having

been defeated by militias a few-hundred strong.

-

30 Mark Bowden, Black Hawk

Down: A Story of Modern War. (New York: Penguin, 2000), 90

-

31 Richard Clarke, Your

Government Failed You: Breaking the Cycle of National

Security Disasters. (New York: HarperCollins Publishers,

2008), 35

Al-Qaeda

leader Osama Bin-Laden missed no time in claiming

responsibility for the U.S. defeat in Somalia. The Saudi

terrorist leader said that he had provided Somali militants

with the sophisticated air-missiles that had shot down the

two Black Hawk helicopters.

He insisted

that U.S. Army had no backbone to fight and die in such

wars.32. He threatened to continue his own

struggle until United States interests all over the world

were in ruins. Thus, the new threat of Islamic radicalism

effectively replaced fifty years of Cold War. This, however,

was a different kind of enemy.

Somalia

always has been a strategic location, but the U.S.

effectively neglected it between Clinton's 1994 pullout and

the advent of the War on Terrorism in 2001. Washington

feared the impact of terrorism growing all around the world,33

particularly in failed states such as Somalia and

Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda threatened more than once that they

would bring their jihad against the U.S. and its regional

ally, Ethiopia. In response, Washington committed another

foreign policy blunder. As allies, it solicited none other

than the Somali warlords who had effectively feudalized and

starved the country. Thus, against its policy and ideals,

the United States effectively legitimized their reign of

terror. In the process of continued feuding for control of

territories, warlords established two semi-autonomous

governments: Somaliland in the northwest and Puntland in the

northeast of Somalia. Southern Somalia, including Mogadishu

and Kismayo, were still lawless - ravaged by clan warfare

and mired in destruction and starvation.34

American's primary goal was to partner any allies in support

of the War on Terrorism in the Horn region.

-

32 Dinesh D'Souza, The

Enemy at Home: The Culture Left and Its Responsibility for

9/11. (New York:

Random House, 2007), 213

-

33 Mathew Blood, "The U.S.

Role in Somali's Misery"; available from http://www.greenleft.org.au/2008/778/39996;

Internet; accessed

25 November 2008

-

34 Ken Menkhaus, State

Collapse in Somalia: Second Thoughts (Review of African

Political Economy, Vol. 30, No. 97, The Horn of Conflict,

Sep., 2003), 406

George W.

Bush came to Oval Office promoting "compassionate

conservatism."35 His balanced, humble foreign

policy outlook quickly changed following the September 11,

2001 terrorist attacks. Starting in December 2001, President

Bush decided to expand U.S. involvement in the Horn of

Africa once again. He declared Ethiopia to be the principal

regional ally against terrorism. Just as Somalia benefited

from U.S. economic aid during the Cold War because of its

strategic location, its neighbor (Ethiopia) now emerged as

favored nation, benefitting from aid from the U.S. Agency

for International Development. Thus, Ethiopian government

and Somali warlords were sought to hunt and neutralize

suspected terrorists hiding in the region.

-

35 David Frum, The Right

Man: The Surprise Presidency of George W. Bush (New York:

Random House, 2003), 5 36 John Prendergast and Colin

Thomas-Jensen, "Blowing the Horn". International Crisis

Group - Foreign Affairs. (March/April 2007). Retrieved

from www.crisisgroup.org/home/index.cfm?id=4679

In Somalia,

Washington endeavored to build a new association: The

Alliance for Restoration of Peace and Counterterrorism. This

was comprised of regional warlords. The United States paid

each $150,000 per month for his cooperation. 36 This type of

unilateral action severely undermined the new transitional

government by further legitimizing states within a state

and, effectively, feudalism. This is not what Somalia

needed; the President of Somali government, Abdullahi Yusuf

Ahmed (who, like some of his ministers, had past lives as a

warlord) continually reiterated the need for U.S. political,

military, and humanitarian aid for his weak government. The

American policy failed, as the Somali people rejected the

coalition between violent warlords and Ethiopia. The former

only brought lawlessness and instability; the latter was

opportunistic at best, and more likely a prospective

colonist. It is no surprise, then, that when conflict

started between U.S. backed warlords and Islamic Court Union

(ICU), the majority of Somalis supported the ICU - seen to

be the only real hope for a peaceful Somalia. Washington's

policy, already a failure, only escalated the crises by

labeling the ICU as extremist and soliciting Ethiopia, a

major recipient of American arms since the Cold War ended,

to deal with the ICU in a sort of proxy war in the grander

scheme of the War on Terror. Of course, U.S. officials

declined to directly address the question of backing for

Somali warlords, who styled themselves as a counterterrorism

coalition in pursuit of continued American support. For

instance, State Department spokesman Sean McCormack vaguely

told reporters:

"The United

States would work with responsible individuals . . . in

fighting terror. It's a real concern of ours - terror taking

root in the Horn of Africa. We don't want to see another

safe haven for terrorists created. Our interest is purely in

seeing Somalia achieve a better day."37

-

37 Emily Wax and Karen

DeYoung, "US Secretly Backing Warlords in

Somalia", Washington Post

17 May, 2006, sec. A01

The United

States' gamble on the warlords failed when the increasingly

well-supported ICU crushed them. The Islamic organization

took control Mogadishu and most of southern Somalia. Now, in

a disastrous blow to U.S. anti-terrorism initiative as a

whole, it revealed its Islamist character. This included the

introduction of a harshly-interpreted Sharia which punished

all outlaws, prohibited the consumption of alcohol and use

of stimulant khat, required women to wear veils, and banned

movies and televised World Cup soccer games on television.

The ICU brand of Islam might have been an abomination in

better times, however most people saw no better choice. The

United States failed to internalize just how unsecure

Somalia had become, when it chose to support the warlords

who had caused this problem. As a reward, it now had an

incredibly hostile governing body to deal with. With the ICU

effectively in power, the country's new, weak transitional

government has been operating largely out of neighboring

Kenya and the southern city of Baidoa. Most of Somalia was

in anarchy, ruled by a patchwork of competing warlords; the

capital was too unsafe for even Prime Minister Ali Muhammad

Ghedi to visit. He described U.S. officials' involvement in

the conflict between Somali warlords and ICU as dangerous

and shortsighted, arguing that this was undermining his

government:

"We would

prefer that the U.S. work with the transitional government

and not with criminals. This is a dangerous game. Somalia is

not a stable place and we want the U.S. in Somalia. But in a

more constructive way. Clearly we have a common objective to

stabilize Somalia, but the U.S. is using the wrong

channels."38

-

38 Emily Wax and Karen

DeYoung, "US Secretly Backing Warlords in Somalia",

Washington Post 17 May, 2006, sec. A01

CHAPTER 3

GLOBAL WAR ON TERROR - POST

9/11

The Rise

of Islamic Movement in Horn of Africa

It has

already been seen that, after the fall of Said Barre in

1991, opportunistic warlords effectively feudalized Somalia

back into a dark age. Their bands ravaged the country amidst

uncontrollable civil war, as they battled for strategic

towns and regional footholds. Anyone who could piece

together an army or militia could obtain a piece of

Somalia.

Accordingly, a group of northeastern Islamists wasted no

time in grabbing Garowe

Town in 1992. While the majority of the Somali population is

Muslim (99%, predominantly Sunni), the nation had long

sustained itself without a theocratic thrust. Religious

leaders have always been respected and honored for their

knowledge of the Islam, yet the Somali culture traditionally

draws a line between their realm and those of state,

government, and clan. Generally, clerics have neither sought

to influence clan politics nor claim any particular

leadership position other than that of teacher.39

39 Metz, 97

Over the

centuries, Somalia pastoral society perpetuated its own

Islamic tradition. Fundamentalism held little appeal for it.

Clan society saw only harm in strict Salafist ideas.

Particularly abrasive among these were rigid Sharia law and

new, rank-and-file leadership which could only confront and

undermine the time-honored clan system. That is why pastoral

Somalia had rejected Islamist militant fervor in the past.

It saw instability rather than tranquility in the usurpation

of power from the most basic social units. It was not easy

for the phenomenon of hard-line Islamism to survive in the

Somali nomadic society without the support of clan leaders,

not to mention the common people as an entirety. However,

fundamentalism - based in sources to which no one could

answer (i.e. the Koran) - was equally hard to squelch

entirely. Like a parasite, it would always find a way to

breed and perpetuate its kind. The Islamist part of Somali

society and its leadership came from different tribes and

regions. However, a single goal unified all of the elements:

to rule the land under Islamic law. The movement was

effectively against all of Somali history. Often construed

as antiquated, fundamentalists actually think themselves

progressive. The Somali version believed that the ancient

clan system was un-Islamic and in need not of realignment,

but abolition. This idea was brash and radical. Its fate in

Garowe Town suggests a basic rift with the Somali people and

time. The clan system brought down the fundamentalists when

northeastern communities learned that the group's principal

leader, Sheikh Hasan Dahir Aways (future head of the Islamic

Court Union), was a member of Hawiye tribe which belongs to

same clan as General Mohamed Farah Aideed. Aideed had

achieved infamy as the notorious warlord who led the rebel

USC in overthrowing Siad Barre's government and instigating

genocide against the Darood clan in the south. Many of the

victims fled from their homes in Mogadishu for refugee camps

in Kenya and Ethiopia.

Well-known

African Horn historian Said Samatar described the

relationship between Islam and Somali tribal tradition as

follows:

"Somalia

will never be a breeding ground for Islamic terrorism" the

main reason being, the Somali politics shaped as it is "to

an extraordinary degree, by a central principle that

overrides all others, namely the phenomenon that social

anthropologists refer to as the segmentary lineage system"40

Exploring

the phenomenon further, Samatar agreed with what Professor

Cassanelli argued about the systematic division among Somali

society:

"My uterine

brother and I against my half brother, my brother and I

against my father, my father's household against my uncle's

household, our two households, against the rest of the

immediate kin, the immediate kin against non-immediate

members of my clan, my clan against others and, finally, my

nation and I against the world." 41

-

40 Samatar, 1992: 629

-

41 Ibid., 629

Accordingly,

Islamist leaders often lost the battle between religious and

clan loyalty. This was the precise fate of the northeastern

Islamists in Garowe Town. Sheikh Aweys looked outside of his

clan to establish and recruit an Islamic militia. He failed.

Local tribal leaders and residents defined him as an

outsider and enemy of the Darood who wanted to unmake the

peace that they had enjoyed since the collapse of central

government. When Aweys and his followers lost the support of

the people, clan warlord and future Somali president

Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed mobilized his militia to oust the

Islamists from Gorowe and the region. That is the best

example of the old clan system overpowering the incursion of

hard-line Islamic ideas.

However, it

was just as difficult to destroy radical Islamism as it was

to defeat the clan system. The movement did not die; rather,

it changed its strategy and point of attack to the southern

regions where there was far more violence, chaos, and

anarchy to exploit. For several years, the Islamists went

underground and quietly reorganized under the radar. Then,

in 1996, they announced a new organization called Al-Itahad

al-Islamiya, based in Gedo in the southwest, near the

Ethiopian and Kenyan borders.42 Here, warlords

and tribal leaders had only a very loose handle. Al-Itahad

al-Islamiya perceived a power vacuum and sought to take

advantage of it. Sheikh Dahir Aweys, previously defeated by

northeastern warlord Abdulahi Yusuf Ahmed in1992, resurfaced

as the organization's leader.43 The radicals

started to collect weapons and impose Sharia on locals

without clan leaders' assent. Before long, Al-Itahad al-Islamiya

had placed its own regional and town administrators in

direct opposition to existing clan leadership. With the

menace growing ever more foreboding, local leaders tried to

negotiate with the Islamists, advising them to lay their

weapons down and resume peaceful teaching duties instead.

The militant group rejected the offer and killed some

influential members of the clan-family to assert that they

were serious. During the negotiations, clan leaders

encountered Islamist's logic and reasoning were beyond their

comprehension, because their rivals sincerely believed that

they did not have any ulterior motives except God's work on

earth and to apply His words to all people and society.

-

42 Andre Le Sage, Prospects

for Al Itihad & Islamist Radicalism in Somalia. ( Review

of African Political Economy, Vol. 28, No. 89,: Taylor &

Francis, 2001), 473

-

43 Chris Tomlinson. "Target

of Somalia air strike was one of the FBI's most wanted."

The Independent. 9 January, 2007.

A long

debate ensued as the southern Somali clan base sought an

appropriate course of action. Mareehaan - Darood warlord

Omar Haji Mohamed, former Defense Minister helped steer the

discussion toward Ethiopia. It was decided to seek military

assistance. Now Sheikh Aweys made another mistake by

operating outside of his Hawiye clan's territory. Combined

Ethiopian and native forces proceeded to defeat the

Islamists in the Gedo region. Al-Itahad al-Islamiya was

essentially nullified as a threat to southern Somalia.

Twice-defeated, Aweys and the remnants of his militia

retreated to Mogadishu, where his Hawiye clan dominates. It

could no longer wage war against any clan militia near the

Somali-Ethiopian border.

The

Islamists were neutralized, but all was not well. Old

problems continued to afflict Somalia. As before, warlords

fought one another for territory, and United States

maintained its distance from the Somali people, who had

suffered a decade of senseless war and drought which had

forced many into refugee camps inside and outside of the

country. Somalia was no longer a country, in truth. It was

split into mini-states controlled by clan leaders concerned

far more with their fiefdoms than national unity government.

Puntland was established as an autonomous region in the

northeast, while the northwest proclaimed its independence

as the Somaliland Republic. The south remained lawless and

violent. The region's deprivation enabled Islamic clerics to

make a comeback as bearers of order and peace. Indeed, the

creation of a new Islamic court system made good on its

promise. The clerics brought some justice to Mogadishu. They

addressed many tough issues, including real estate and other

civil disputes around which clan warfare had revolved.

Mogadishu, at least, saw a drop in clan feuds and criminal

activities.44 As a result of this, the Hawiye

clan-family, which had suffered greatly at the hands of

warlords, grew to support the Islamic clerics as a possible

check to harmful warlords' influence within the clan-family.

The clerics' potential for stabilization was apparent,

insofar as their main goal was to advance and protect the

interests of the tribe. Unfortunately, Islamic extremism has

shown again and again that this is too much to hope for.

While Islamic clerics committed themselves to community

service and fair judgment by law, they had bigger agenda

than their own local clan in mind: to introduce Sharia and

to rule first Mogadishu and then all of Somalia by Islamic

law. With the full support of their clan-family and its

leaders, the clerics had an opportunity to organize former

Al-Itihad al-Islamiya members and sympathizers into a court

militia, charged with enforcing rulings and arrest runaway

criminals. The arming of the court gave it enormous autonomy

and justification, bordering on martial law. In 2006,

Islamic clerics and businesspeople progressed further in

forming a new political organization called the Islamic

Court Union (ICU) to unite all smaller Islamic groups.

Electing 90 assembly members helped legitimize the Islamist

interest. As president, they elected none other than former

Al-Itihad al-Islamiya leader Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys.

Aweys had twice failed in efforts to Islamize large chunks

of Somalia. Now, with a political apparatus and established

court behind him, he once again pushed into the south.

-

44 D. Ignatius, "Ethiopia's

Iraq. Washington Post," 13 May 2007 , sec. B07

Since

Somalia was classified as failed state and had lost its

territorial integrity soon after the collapse of central

government fifteen years earlier, the Bush administration

overreacted to this new development by employing warlords to

fight an American proxy war under the heading of the War on

Terrorism. Bush declared Somalia a potential "haven of

terrorism"; there was, in truth, a precedent to back this

opinion. Al-Qaeda and non-state actors favor a lawless and

anarchic environment where they can conduct training,

operate their financial and communication networks, and plan

targets relatively freely. In Somalia as well as

Afghanistan, Al-Qaeda recruited from the local population

and preached openly its opportunistic "destroy-and-kill"

philosophy. The indoctrination and manipulation of young,

disenchanted Muslim men has been an effective a strategy.

Peace-loving people around the world have been materially

and morally robbed - too often of life itself. Osama bin

Laden's al-Qaeda deserves the greatest condemnation for its

barbaric actions and needs to be eliminated as an entity by

any means possible. However, it remains the case that

Somalia is not the same situation as Afghanistan. Here

again, as with Iraq, the Bush administration automatically

associated trouble and unfavorable circumstances in a Muslim

country with al-Qaeda and terrorism. The U.S. branded the

ICU without learning about the complex relationships between

Islamic clerics within the ICU organization. In reality the

organization, like Islam itself, is very multifaceted.

Besides the different factions loyal to specific ethnic

groups, ICU militants and clerics pursued and advocated

different varieties of Islam. These include but are not

limited to traditionalist, Brotherhood, Salafist, Islamist,

and Jihadist Muslim. Washington missed a great opportunity

to recognize these differences and choose its words,

actions, and judgments accordingly. By branding the entire

ICU as "terrorist," the U.S. alienated Somali Muslims in

general and forged a much greater enemy in the process.45

Thus, unwelcome American incursion only helped to encourage

the ICU's rise to power. Three factors behind its rise were:

1.) Violent turmoil and lawlessness which killed many

Somalis and denied many more the right and ability to work

and feed themselves. 2) Lack of international support in

addressing the need for national reconciliation in forming

an inclusive, credible government. 3) The United States and

its Ethiopia ally rushing to judgment in characterizing all

devoted Somali Muslims as radical Jihadists in need of

destruction.

-

45 Anna Shoup, "U.S.

Involvement in Somalia"; available from www.pbs.org/newshour/indepth_coverage/africa/somalia/usinvolvementinsomalia;

Internet; access 24 November 2008

Washington,

in failing to understand the importance of the above issues,

missed an opportunity to better its international image and

Somalia. Addressing the ICU with care - via diplomacy and

international consensus building - might have gone a long

way in easing the United States' reputation for stereotyping

and not quite trying to understand Muslims (or worse, being

their enemy). The Islamic world and Africa might have been

well-involved in a concerted effort to stabilize Somali.

Instead, the U.S. went the route of facilitating more war in

a war-torn nation. By financing Ethiopia and Somali warlords

in their fight against the Islamists, Washington was

perceived by Somalis not as the solution, but part of the

problem. In fact, the underhanded maneuvering of

Kenyan-based CIA operatives made the extremists more

popular, boosting their image as righteous warriors among

radicals and traditionalists alike. It is probably not

coincidental, therefore, that before Mogadishu fell into the

hands of the ICU and imposed a strict interpretation of

Sharia law. Washington was alarmed; it would seem that

Somalia had acquired its own Taliban.46

Somali

expert and associate professor of political science at

Davidson College in North Carolina, Ken Menkhaus, lamented

the consequences of the turn in U.S. Somali policy: " This

is worse than the worst-case scenarios - the exact opposite

of what the US government strategy, if there was one, would

have wanted". 47 Washington, in many ways, made

its own bed; now it will have to lie in it. It had paid

little attention to a decade-long humanitarian crisis,

anarchy, and lawlessness. To this day, the U.S. State

Department Bureau of African Affairs webpage does not even

include Somalia as a trouble spot in sub-Saharan Africa in

need of help and attention. In short, the U.S. has no

inherent political and economic interest in Somalia which

requires it to intervene for peace and stability. However,

as the second Islamic radicalism comes to the fore, the U.S.

shifts its policy and pursues a quick-fix marred war and a

further exacerbation of the crisis. All of this begs a very

good question: Is the United States really involved in

Somalia for Somalia's sake, or for its own?

-

46 Burkheman, O. (2006,

June 10). Fall of Mogadishu Leaves U.S. Policy in Ruins.

Guardian, pp.A4

-

47 Ibid, pp.A5

The United

States' dilemma grew and contracted some additional urgency

when Al-Itahad al-Islamiya leader Sheikh Aweys took control

the ICU organization. Naturally, Al-Itahad al-Islamiya was

added to the list of al-Qaeda-linked terrorist

organizations.

The

Ethiopian government had accused Aweys' group of involvement

in a series of bombing in Ethiopia. During a congressional

hearing, Jendayi Frazer, Assistant Secretary for African

Affairs, told lawmakers that the U.S. would monitor the

situation and coordinate a response through a new body

called the Contact Group. The Contact Group consists of the

African Union (AU), United Nations (UN), European Union (EU),

United States, Sweden, Norway, Italy, Tanzania, and others.

Frazer explained the ICU takeover of Mogadishu and other

southern towns as an extension of al-Qaeda operations: "The

U.S. government remains deeply troubled by the foreign-born

terrorists who have found safe haven in Somalia in recent

years."48 The U.S. drafted a U.N. resolution that

authorized the African Union (AU) to intervene in Somalia

and asked the international community to finance this

effort. On December 6, 2006, the Security Council passed

resolution number 1725. Predictably, the Ethiopian army,

with complicit U.S. backing, rushed in to protect the United

Nations-sponsored Transitional Federal Government (TFG),

based in Baidoa, a small town in the Northwestern Bay

region.

-

48 Council on Foreign

Relations (2007, August, 22). Ethiopia - Eritrea Conflict

Fueling Somalia Crisis. Retrieved November 24, 2008,

Retrieved from http://cfr/publication /14074/lyons.html

Thus, the

U.S. and its Ethiopian ally decided to resolve this Somali

crisis by force. Their ICU rival responded with an ultimatum

demanding the departure of the Ethiopian troops from Somalia

within seven days; failure to do so would result in a holy

war against the Ethiopian government. Predictably, these

demands were not met. On December 20, 2006, a full-scale war

broke out between the Ethiopian army and ICU militants near

Baidoa, the temporary TFG administrative center. The ICU was

defeated within a couple of weeks, as Ethiopian

professionalism overwhelmed the essentially amateur rebel

militia.49 The ICU still did not fall back on its

promise, however. Its leadership and forces retreated to

different parts of the country, where they resumed their

"holy war" via guerilla tactics. This Iraqi-style insurgency

was most significant in Mogadishu. Ethiopia was the United

States' most important East African ally in the fight

against international Islamic terrorism. America's purpose

is relatively clear, but what was Ethiopia's motive? One can

be certain that there was more to its interest in Somalia

than mere terrorism. Here the past may enlighten the future.

The Role of Ethiopia in Somalia

-

49 J. McLure, "Meles Zenawi:

An Important All." News Week, 21 April 2008. Retrieved

November 24, 2008, from http:/www.newsweek.com/id/131703

Ethiopia has

always had a political and strategic interest in Somalia and

would never remain indifferent or oblivious to any crisis in

Somalia. Geographically, whatever happens in Somalia

invariably affects Ethiopia and other neighboring countries.

The relationship between the two nations has been tense over

the centuries. The boiling point, however, is rather recent.

Specifically, the 19 th century hosted Ethiopian annexation

of ethnic Oromos and Somali territories. During this period,

Emperor Menelik II not only defended

Ethiopia

against European colonies, but also competed with them for

Somali-inhabited territories which he argued to be

legitimately Ethiopian. By the turn of the 20th century,

Somali was divided into British, French, Italian, and

Ethiopian (the Ogaden) Somaliland, and what later to be

named the Northern Frontier District (NFD) of Kenya. It is

important to note that all Somalis share the same language,

culture, religion and blood.50 In fact, Somalis

form one of the most homogeneous peoples in Africa. As

mentioned, Sayyid Mohammad Abdille Hasan and his army formed

a guerilla defense against both British and Ethiopian

authorities. However, the conflict between Somalia and

Ethiopia did not start in earnest until the 20th century.

For instance, King of Negash Yeshak (1414 - 1429) of

Ethiopia stated in one of his victory songs about the

defeated Somali groups in the Islamic Sultanate of Aden,

Northern Somalia.51

Somalis form

one people, but it took a long time for them to form one

nation. In fact, the first time that all Somali ethnic

territories united was in the 1930s, when Italian premier

Benito Mussolini's armies invaded Ethiopia, ousted Emperor

Haile Selassie, and conquered British Somaliland. Italian

occupation lasted only one year (1940-41). This is because,

for the first time in forty years, Somali clan families

united and forgot the artificial boundaries drawn by Anglo,

Italian, and Ethiopian occupiers.52 However, the British

quickly reaped the rewards of Italy's botched East African

colonial experiment. They retook lost territory from the

Italian army, reoccupied northern Somalia, and restored

Emperor Haile Selasie to his throne. Then they went further,

taking the opportunity to impose military administration in

southern Somalia and the Ogaden.53

-

50 Braine, 436

-

51 Ali Jimale Ahmed, ed.

The Invention of Somalia (NJ.: The Red Sea Press, 1995),

82.

-

52 I. M. Lewis, A Modern

History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa.

(London: Westview Press, 1988), 116

-

53 Ogaden region is the

home of Somali ethnic group and the purpose was named

Ogaden in this region (Ogaden is one of the Somali clan

families) was to create division and conflict within the

Somali tribes in this territory.

After

intense pressure from Haile Selasie, the British gave the

Ogaden back to Ethiopian jurisdiction but retained their

position in the south.

Initially,

Washington decided not to get involved in European imperial

maneuvering in Africa, but the Italian invasion of Ethiopia

challenged Washington's neutral position. The United States

refused to recognize the Italian conquest and imposed an

embargo on its government.54 This new, more vocal

policy gave Ethiopian's exiled Emperor Haile Selasie the

chance to forge a new relationship with the U.S.

- 54 Jeffrey

A. Lefebvre, Armies for the Horn: U.S. Security Policy in

Ethiopia and Somalia 1953 - 1991 (University of Pittsburg,

1991), 67 55 Lefebvre, 68 56 Ibid., 69 57 Ibid., 74

Washington

announced a plan to provide economic aid to Ethiopia and

help train the Ethiopian army. In return, the U.S. fleet was

granted the right to continue utilizing an existing military

facility in the former Italian colony of Eritrea. This

mutual relationship provided Ethiopia with approximately $5

million in military aid and forgave most of its debt,

reducing it from $5 million to $200,000. 55 Other

benefits included formal military training and the full

equipment of 1,000 enlisted men and officers.56

Essentially, all of this amounted to a trade of what either

party could provide for what it needed: arms to Ethiopia and

a regional base for the United States.57

Haile

Selasie's military buildup was not a random or unprovoked

movement; it had very practical roots to the east in

neighboring Somalia, which remained unhappily colonized

after the World War II. Selasie warned that Somalis were not

only Muslims, but communist sympathizers. He preyed on

America's fears to lure its interest and aid. Emperor

Selasie was a skillful statesman politician who understood

world politics in terms of balance of power and competition

between the U.S. and Soviet Union. He played them well

against each other. For instance, he convinced the U.S.

administration under President Henry Truman in 1948 that

U.S. security interests would be best served if the Italian

colony in Eritrea be absorbed into Ethiopia.58

The reason that the U.S. rejected the Italian trusteeship in

Eritrea was that the Italian government was weakened and

unstable; therefore, it was easily susceptible to communist

and Soviet interference. This formula having worked, the

Emperor wasted no time in portraying Somalia (still under

the British protectorate) the same way, and vigorously

pushed Washington, Britain, and the United Nations to yield

the Haud and Reserve area, part of the Ogaden region, to the

Ethiopian crown.59 The Eisenhower administration

was receptive. Catering to Selasie's concerns - real or

contrived - was a means to a greater end: the Cold War, and

the acquisition of Ethiopia as an ally against any potential

communist enemy in the region.

Emperor

Selasie rekindled and reinforced the animosity between

Somalia and Ethiopia largely as an act of Cold War

opportunism. 60 With American support, his

geopolitical ambition of being the relative "superpower" in

the region was fulfilled. Then, in 1960, Somalia earned its

independence. Understandably, the young nation's first

priority was to acquire military hardware from different

sources in order to defend itself from Ethiopian domination

in the region. The rival Horn nations' simultaneous

militarization caused two wars, in 1964 and 1977. Thus,

Ethiopia and Somalia spent billions of dollars and engaged

in costly conflicts while millions of their people died of

famine and starvation or were forced into neighboring

countries, North America, and Europe as refugees. Indeed,

the entire region suffered. Both countries' per capita GDP

was less than $300. Both neglected the benefit of health and

education services for their citizens; rather, they diverted

their nation's resources and foreign aid to their war

machines, purchasing sophisticated weapons for use against

each other's people. Somalia's standing army increased from

16,000 in 1960s to 54,000 in 1976. Ethiopia was not much

better equipped for war. Over the same period, Ethiopia

managed with its 40,000-45,000 man army, navy, and air

force. This was, however, before the Marxist-Leninist

Mengistu Haile Mariam regime (1975-91), when the army hit

300,000. 61As it turns out, the jostling of the Eisenhower

years and 60s was but a prelude. Ethiopia has imported well

over $10 billion worth of arms since World War II, but more

than 95 percent of this has came from the Soviet Union after

the 1977 Somali-Ethiopian war.

-

58 Lefebvre, 66

-

59 Somalia's interest was

always to incorporate the Somali - inhabited Ogaden region

of Ethiopia into a Greater Somali.

-

60 Fred Halliday, US Policy

in the Horn of Africa:

Aboulia or Proxy Intervention (Review of African Political

Economy, No. 10 (Taylor

& Francis, Ltd. Sep. - Dec., 1977), 10

-

61 Reported in David Korn,

Ethiopia, the United States and

Soviet Union

(Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University

Press, 1986), 32

Somalia

started the senseless war of 1977, responsible for thousands

of innocent lives lost and the proliferation of refugees.

This conflict was essentially an act of idealism.

Specifically, the Siad Barre government sought to

incorporate the Somali inhabited Ogaden region, controlled

by Ethiopia, into a Greater Somalia. Somalia, as a Soviet

Union client during the Cold War, accumulated over $2

billion dollars worth of sophisticated weapons thanks to the

Eastern bloc. As result, while the Somali National Army (SNA)

was outnumbered by Ethiopian forces by as many as 35,000

men, it had three times the tank forces and a larger air

force.

Somalia's

Soviet relationship essentially contradicted history.

Ethiopia had typically enjoyed geopolitical dominance in the

Horn of Africa. Now, for the first time, the balance of

power tilted toward Somalia. Thanks to Cold War superpower

maneuvering, Ethiopia grew weaker while Somalia found

substantial military strength. However, Siad Barre

miscalculated the balance of power between the Soviet Union

and United States of America when he attempted to take

advantage of Ethiopia's political instability. Ethiopia

encountered hard times when long-standing Emperor Haile

Selassie was overthrown by the Derg (military council),

resulting in political turmoil and a battle for ultimate

supremacy over the ruling junta. Some elements of Somali

society took advantage of this distraction to pursue their

own ends. Most notable were the Somalis of the Ogaden,

overwhelmingly frustrated with what they saw as foreign

rule. A group called the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF)

materialized to bear their flag. The rebels engaged Ethiopia

in an armed struggle for the end of colonialism and reunion

with the Somali nation, which aided the cause.62

-

62 I. M. Lewis, A Modern

History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa,

4th ed., (London: Westview Press, 1980), 243

The Soviet

Union, with close ties to the Siad Barre government,

observed the development of this conflict with interest. As

important as what was happening between Somalia and Ethiopia

was the internal struggle within the Ethiopian Derg. Its

result would change the region again. Mengistu Haile Marian

maneuvered his way to supremacy over the Derg. He was

proclaimed head of state in February 1977. Thus, the Soviet

Union secured another client in the Horn of Africa as the

new leader's Marxist-Leninist orientation became clear.

Mengistu courted the Soviets symbolically, ordering the

United States out of Ethiopia by April 1977.63

For Somalia, the mathematics of this arrangement were

precarious. If Somalia and Ethiopia were enemies, the Soviet

Union could not reasonably support both. Logically, it would

choose the stronger.

With

Mengistu's rise, the U.S. lost Ethiopia to the Soviet Union.

However, Ethiopia and the Soviet Unions' shift opened a new

opportunity for American strategic interest in East Africa.

It started when Said Barre decided to make a decisive

military campaign by invading the Ogaden region in July 13,

1977. The Soviet Union, seeking the best foothold possible

in the region, made every effort to work out some sort of

Somali-Ethiopian ceasefire. With the war escalating, the

Soviet Union was still supplying both sides while trying to

convince Siad Barre to withdraw his forces and accept a

peaceful resolution to the crisis. This effort failed.

64 Siad Barre was more interested in Somali hegemony

than Soviet assistance; the latter had been but a means to

an end. Now the Soviet path was clear. The communist

superpower abandoned Somalia and shifted all aid and support

to Ethiopia. The shift came at a critical time in the

Somali-Ethiopian war. Almost 60 percent of Ogaden region was

behind Somali lines, including the strategic location of

Gode on the Shabelle River. Having already alienated

Somalia, the stakes were high for the Soviet Union. If

Somali success continued and the Marxists were brought to

humility, it would be left empty-handed in East Africa.

Accordingly, the USSR rushed to Ethiopia's support before

the new Marxist regime collapsed. It flooded the nation with

military advisors while Cuba supplied 15,000 combat

troops.65 Military aid was virtually unlimited, second only

to that provided to Syria during the Yom Kippur war. Other

countries made similar contributions to the cause of

stopping Siad Barre, including North Korea, the People's

Democratic Republic of Yemen, and East Germany.66Siad Barre

had no future with the Soviet Union and wasted no time in

expelling Soviet remnants from Somalia and severing

diplomatic relations.

-

63 I. M. Lewis, A Modern

History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa,

4th ed., (London: Westview Press, 1980), 233

-

64 Robert D. Kaplan,

Surrender or Starve: The War Behind the Famine (London:

Westview Press, 1988), 154

-

65 Metz, 183

-

66 Wiberg, H., The Horn of

Africa. Journal of

Peace Research: Vol. 16, No. 3. (Saga Publications, 1979),

191.

-

67 Lewis, 1980: 234

The cost of

this war was enormous in lives and resources for two of the

world's poorer countries. The Ethiopian government managed

to quickly recruit a roughly 100,000-strong militia to

integrate into its regular fighting force, while Somalia

itself raised 80,000 for the advancement of its attacks

toward the gates of Jigjiga and Harar. 67

Somalia, however, was not able to push its advantage. Things

were beginning to shift due to heavy losses in tank

battalions, persistent and precise Ethiopian attacks upon

supply routes, and the difficulty of moving equipment during

the rainy season. It was an unwise war from the start. Siad

Barre was beginning to sense its consequences. His army