|

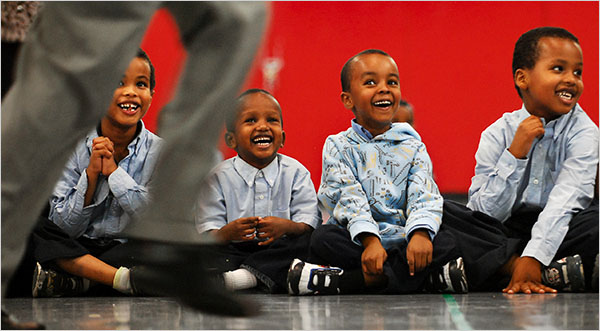

Immigrants See

Charter Schools as a Haven

(Minneapolis, January,

10 2009 Ceegaag Online)

Fartun Warsame, a Somali immigrant, thought she was being

a good mother when she transferred her five boys to a top

elementary school in an affluent Minneapolis suburb. Besides

its academic advantages, the school was close to her job as

an ultrasound technician, so if the teachers called, she

could get there right away.

“Immediately they changed,” Ms. Warsame said of her sons.

“They wanted to wear shorts. They’d say, ‘Buy me this.’ I

said, ‘Where did you guys get this idea you can control

me?’ ”

Her sons informed her that this was the way things were

in America. But not in this Somali mother’s house. She soon

moved them back to the city, to the International Elementary

School, a charter school of about 560 pupils in downtown

Minneapolis founded by leaders of the city’s large East

African community. The extra commuting time was worth the

return to the old order: five well-behaved sons, and one

all-powerful mother.

Charter schools, which are publicly financed but

independently run, were conceived as a way to improve

academic performance. But for immigrant families, they have

also become havens where their children are shielded from

the American youth culture that pervades large district

schools.

The curriculum at the Twin Cities

International Elementary School, and at its partner middle

school and high school, is similar to that of other public

schools with high academic goals. But at Twin Cities

International the girls say they can freely wear head

scarves without being teased, the lunchroom serves food that

meets the dietary requirements of Muslims, and in every

classroom there are East African teaching assistants who

understand the needs of students who may have spent years in

refugee camps. Twin Cities International students are from

Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and Sudan, with a small population

from the Middle East.

Amid the wave of immigration that has been reshaping

Minnesota for more than three decades, the International

schools are among 30 of the state’s 138 charter schools that

are focused mostly on students from specific immigrant or

ethnic groups. To visit a half-dozen of these schools, to

listen to teachers, administrators and parents — Somali

immigrants who are relatively new to Minnesota, as well as

the Hmong and Latinos who have been in the state for decades

— is to understand that Ms. Warsame’s high educational

aspirations for her children, and her fears, are universal.

“The good news is that immigrant kids are learning

English better and faster than ever before in U.S. history,”

said Marcelo M. Suárez-Orozco, the co-director of

immigration studies at New York University and co-author of

“Learning a New Land — Immigrant Students in American

Society” (Harvard Press, 2008). “But they’re assimilating to

a society that parents see as very threatening and

frightening. It’s anti-authority, anti-studying. It’s

materialistic.”

Some critics argue that these kinds

of charter schools are contributing to a growing

re-segregation of public education, and that they run

counter to the long-held idea of public schools as the

primary institution of the so-called “melting pot,” the

engine that forges a common American identity among

immigrants from many countries.

“One of the primary reasons that American society

supports public schools is to give everyone a solid civic

education,” said Diane Ravitch, an education historian, “the

sort of education that comes from learning together with

others from different backgrounds.”

But Dr. Suárez-Orozco says the reality is that most new

immigrants become isolated in public schools, and that large

numbers of them become alienated over time and fail to

graduate.

A place like Minnesota, with its strong charter-school

movement, offers immigrant parents, who have long been

conflicted about their children becoming Americanized, a

strong voice in their children’s education, Dr. Suárez-Orozco

said, and shows their eagerness to participate in democracy.

“What the parents are saying,” he said, “is, We want our

children to assimilate, we want them to acculturate, but we

want to be proactively engaged in shaping that process.”

Ali Somo, a 70-year-old father of three children at the

International Schools, put it this way: “We bring our

children here because we want them close to us so they don’t

get lost.”

It was a weekday morning, but Mr.

Somo and Ms. Warsame and a group of other parents, some

holding down double shifts as cabdrivers, hotel

housekeepers, and parking lot attendants, were squeezing in

a meeting in the school library, with its shelves lined with

“Huckleberry Finn,” “The Red Badge of Courage,” “Little

House on the Prairie” and other American classics.

Getting lost in America, Mr. Somo explained, means losing

your culture, your language, your identity. It means acting

like the teenagers the parents see on the street — wearing

baggy jeans, smoking, using drugs, disrespecting elders.

“I have been in America, and I have observed,” Mr. Somo

testified. “I have seen children with their pants falling

off. I have seen them doing drugs.”

The parents around him nodded. Another father, Jelil

Abdella, talked about how it saddened him that his two grown

children, who had attended large district schools, did not

know how to speak Somali. “They’re neither American, nor

Somali,” Mr. Abdella said.

As a newcomer, he said, he was too busy going to school

and earning a living — driving a taxi, cleaning floors,

working in a factory, picking blueberries — to supervise

their educations closely.

“I don’t want to make the same mistake with my younger

children,” he said. “I want them to keep the good things we

used to have back home — respecting their parents, helping

each other, respecting their elders.”

Another father, Mahamaud Wardere,

said: “It is important that they all know they’re American.

It is equally important that they know they’re Somali.”

It is this dual identity that the International Schools

work to encourage. There are lessons in snowshoeing and

baseball, and field trips to the Mall of America, where

instead of shopping, the students participate in another

American ritual, the charity fund-raising walk. There are

also teen-agers complaining that their parents worry too

much.

“I can at least account for more than 200 lectures I’ve

had from my mom and dad about American culture here,” said

Omar Ahmed, a 14-year-old eighth grader. “My dad always

says, ‘Back in Somalia, when I was 14, I could see myself

running my own business, having my own children. You’re 14,

you can’t get your studies done.’ ”

“Every time my mom sees something bad about teens in the

news,” Omar said, “there’s another lecture on that subject.”

Perhaps nothing more vividly demonstrated the students’

enthusiasm for American democracy than a debate this fall in

Elizabeth Veldman’s eighth-grade social studies class about

the presidential race. The two teams of students had spent

days preparing.

“Look at our history — look at what

happened with the Vietnam War,” said Yaqub Ali, 13, a

fervent supporter of Senator John McCain who arrived four

years ago from a Somalian refugee camp in Kenya, knowing no

English. “Do you want to lose a war?”

“Sit down, Yaqub!” commanded Ridwa Yakob, who describes

herself as “a girl who loves to talk.” She argued that

Senator Barack Obama would fix everything from education to

the economy.

Yaqub, wearing a dark suit for the occasion, rose again.

“John McCain is old,” he said. “It is better to be old.”

At the International school, where elders are revered,

even Ridwa was silenced.

At their meeting, the parents talked of the importance of

speaking English at school — and Somali or Oromo at home. At

other charter schools, Hmong refugee and Latino parents

expressed the same wish, the difference being that they want

their children to speak Hmong, or Spanish, at home, the

other difference being that many of their children are

already so Americanized that they are learning their

parents’ languages in school.

“The other day a spider fell from the roof and my son

picked it up,” Mr. Somo said, referring to his 13-year-old,

Hussein. “What do you call it in English, I asked him. He

told me. How to say it in Oromo — I told him myself. How to

say it in Arabic and Somali — he learned it himself. He was

able to say the word for “spider” in four languages.”

With that kind of linguistic talent, Mr. Somo said of his

son, “he can work for America anywhere in the world.”

Dr. Suárez-Orozco said: “What these parents are doing, in

taking ownership of their children’s schools, is as American

as apple pie. They’re doing what soccer moms and dads in

Lexington, Mass., and Concord and Cambridge do day in and

day out. They’re modeling for kids the story of

acculturation and how it works.”

Source: AP

webmaster@ceegaag.com |